|

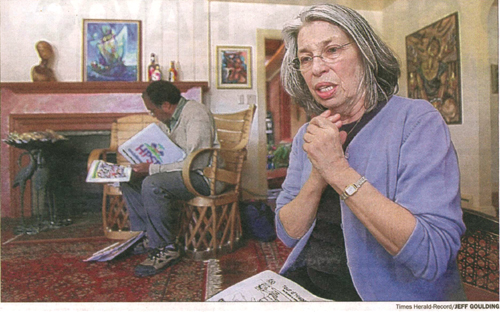

Woodstock group helps plant hope in HaitiA local organization, the Haitian People’s Support Project, co-founded by Terry Leroy and her husband, Pierre Leroy of Ulster County, is among several supported by local residents to help Haitians who were displaced and are still struggling after the 2010 earthquake. Terry poses with a painting by a Haitian artist.CHET GORDON/Times Herald-Record

By James Nani

Times Herald-Record

Published: 2:00 AM – 04/02/12

Plant by plant, dollar by dollar, those in our region continue to reach out to Haiti two years after a devastating earthquake in 2010 left tens of thousands dead and more injured and homeless. Donations from Hudson Valley residents since last year have helped plant more than a quarter million “miracle plants” in Haiti — a tree known as the moringa that is coveted by humanitarian groups for its high nutrient content. Since last year, The Haitian People’s Support Project, based in the Town of Woodstock, has raised money for, and helped plant, 300,000 moringas. Their goal is 400,000 every year. “The moringa is amazing,” said Terry Leroy, who’s been running the nonprofit with her husband, Pierre Leroy, for 22 years. Much of the plant is edible, including seeds, pods and leaves. According to the group, the moringa has seven times the vitamin C of an orange, four times the vitamin A of a carrot, and twice the protein of yogurt. Plus, it grows like a weed. “The organization has been sustained through the people of the Hudson Valley,” said Leroy. She said residents of the region have donated about $40,000 so far in the effort. The reforestation project is aimed at providing nutrition, stability and work to Haitians, which, in recent years has been a particular need. Other groups help, tooReconstruction has been hindered on the island due to turmoil in the still-fragile government. In February, Prime Minister Garry Conille resigned because of conflicts with President Michel Martelly. Last week, a United Nations official urged Haitian authorities to revive a reconstruction commission that was dissolved in October. The commission was in charge of coordinating rebuilding efforts after the earthquake. “It’s hard, because it’s all uncertain,” said Leroy, referring to Haiti’s political situation. The foundation run by the Leroys isn’t the only organization reaching out to Haiti that’s supported by locals. Carl Braunagel, owner of Aliton’s Pharmacy in Port Jervis, has donated medicine and medical supplies for church missions to Haiti through the Humbled Helping Ministry. He’s heading there, along with other nearby residents, on April 15 to assist in person. Braunagel said he was inspired to do more after a trip to Ghana. “We have no idea how lucky we are,” he said. Middletown resident Maria Blon said Wings over Haiti has also helped since the earthquake by buying land, drilling for water and building a school. Blon said it’s easy to forget that Haiti is just a four-hour flight from New York. “What we found is that these non-governmental groups are making the difference,” said Blon. Art sale in New Paltz to benefit Haitian People’s Support Project

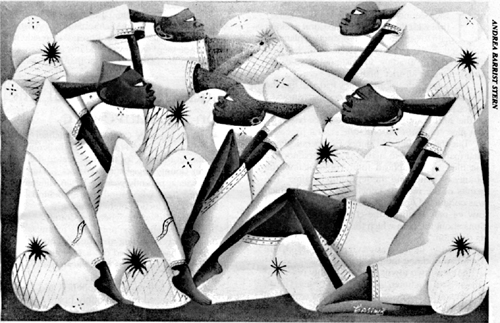

Haiti’s new school of modern art is being exhibited in venues around the US and Latin America in a traveling show that landed in New Paltz last month. Currently hanging in the Cafeteria coffeehouse on Main Street are works by five well-known Haitian artists who represent FAPADEC, the National Haitian Artists’/Painters’ Association. Featured artists include Thebaud David, Myke Joseph Surpris, Osse Hermantin, Sonel Guerrier, Addmaster Exilas, Dorvil and Faustin, all of whom are teacher/volunteers at the art school Espwa Lavi Pou Timoun (ELT), Hope for Children’s Lives, located in a suburb of Port-au-Prince. Working collaboratively, they have put their murals on Haiti’s most famous nightspots, including the Olfson Hotel. The art show is curated by local musician/music therapist/photographer Peter Crotty to benefit the Haitian People’s Support Project (HPSP), a not-for-profit organization dedicated to helping the people of Haiti through existing grassroots, community-based projects there. Founded in Woodstock in 1990 by Pierre and Terry Leroy, HPSP backs sustainable living, nutritional and educational programs in farming communities, orphanages, schools and temporary shelters throughout Haiti. A massive reforestation project in Bois Neuf will help reforest Haiti and combat malnutrition. And of course, continuing efforts to assist survivors of the January 12, 2010 earthquake in and around Port-au-Prince are of primary importance. Crotty and his partner Halle Kananack organized a tent collection at Mountain Jam last year to donate to HPSP for earthquake victims, and when they delivered the tents to the Leroys, they were impressed with the art hanging in the couple’s Woodstock home. With his experience organizing Fourth Saturdays in New Paltz and curating art shows for Jim Szetz during the Cafeteria’s past incarnation as the Muddy Cup, Crotty made arrangements there for this exhibit of works by the Haitian artists. All proceeds from sales are going to HPSP, making hot lunches and drinking water and other support services available to the impoverished students at ELT. Crotty and Kananack extend a heartfelt shout-out to Szetz for his generosity in hosting the show, and hope that the community comes in to appreciate the artwork and learn more about HPSP. For more information about HPSP, visit haitiansupportproject.org or contact co-founder and director Terry Leroy at (845) 679-7320. For pricing information and other inquiries, please speak with Peter Crotty at (914) 213-0046 or eddimusic@hotmail.com.

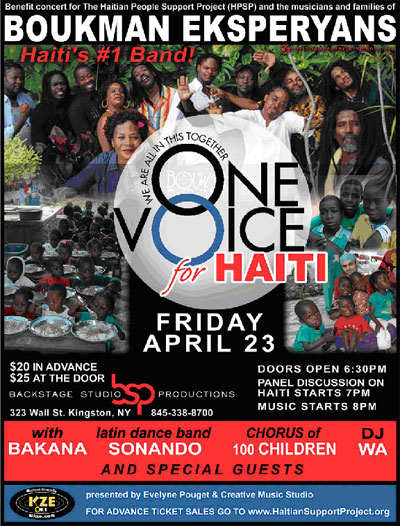

Boukman Eksperyans Benefit Brings Hope to HaitiThis article appeared in Vanity Fair’s online issue of 4/23/2010 Boukman Eksperyans Benefit Brings Hope to Haiti

For several decades now, the Haitian band Boukman Eksperyans has been a force to be reckoned with—a high-energy, eleven-piece ensemble that mixes vodou rhythms with elements of rock, reggae, and African roots music. (The band’s name is a reference to both a vodou priest of the Haitian Revolution and guitar-idol Jimi Hendrix—“eksperyans” is Creole for “experience.”) Since 1990 at least, when their Carnival hit song “Ke’m Pa Sote” became a protest anthem against the post-Duvalier military regime, the band has also been a powerful voice for change in Haiti. The band’s founder and leader, Theodore “Lolo” Beabrun, is a musical soul-rebel in the tradition of Bob Marley and Fela; and in the aftermath of January’s devastating earthquake, his mission has become all the more urgent. This Friday, the band will perform in Kingston, New York, in a special “One Voice for Haiti” concert benefitting The Haitian People Support Project, a Hudson Valley-based relief organization; and Monday they will return for a show at their long-time New York City stomping grounds, SOB’s. VF Daily spoke by phone with Beabrun as he prepared for a lecture and concert at the University of Michigan last week—his first trip out of the country since the earthquake. Less an interview than a stream-of-consciousness-raising cri de coeur, Beaubrun shared with us his vision for a new, reconstructed Haiti. Chant Down Babylon Beaubrun: Since 1990, as a band, we’ve been in confrontation with the army in Haiti. They’ve always tried to silence us, but they never could. They tried in many ways, but with the help of the spirit we’re still here, we’re still fighting. We take our movement to the streets, we take part in demonstrations; but we’re not part of any political regime, we never support any political party. Because what is important for us is to change the system, not to help any one political party take power. We’ve had amazing support around the world, but also from the Haitian people. They know we’re there to give them the message when they need it. That’s why every year at Carnival, they’re waiting to hear our music to know what to do, waiting for our music to act. This year, of course, it was impossible to have a Carnival—it was too close to the disaster…. But, you know, Carnival is good for the people, it’s like a therapy, it releases the energy they cannot control. It helps them. During the Carnival, the people are free to sing, to dance; and through the singing, the dancing, they release their frustration, their energy. I hope we will find another way to express that frustration now. Movement of the People Actually, what’s on my mind right now is to find real skilled help for our country: to build houses for people, to build schools and hospitals. So I’m working with several grassroots groups on this. But what I think we really need is a new mentality, another way to see things. We’re talking about a new way to see Haiti. For example, the two forms of medicine—the bush medicine and the modern medicine—need to work together. We just did a seminar on these two forms of medicine; and when we go back we’ll do more of these programs, where we bring in real bush doctors to tell us their experiences, how they do things. Also, we need new ways of looking at education. Similarly, we’re planning to do seminars on Montessori education. We have a movement we call “Eyes on the Nation,” a movement to bring about a new Haiti. We actually started it a long, long time ago. We’re not politicians; it’s a movement to empower citizens to get their ideas out. For me, it’s a spiritual revolution that will help create all the other changes we need: social, political, economic. But it has to be spiritual first. It has to come from the heart of the people. That’s why when I go back to Haiti I’m going to go and speak out all over the country and say we need to build the new society, the new Haiti. Because, you see, the old Haiti has let us down; and after the earthquake it’s actually collapsed—the buildings, the institutions, the political system. The earthquake has become a symbol for us, a symbol of the corpse our society has become. That’s why we say we have to change things. Now, after the earthquake and the demolition of all those buildings, is the time to transform the country. We’re at a crossroads; it’s a time to choose which way forward for ourselves. Another Haitian Revolution The power has to be in the hands of the whole people—this is the real democracy. We’re a big country with forty-three provinces that need to share in the power, the money of the country. The money has to go to all forty-three provinces. Each one needs to have at least one big hospital with 1,000 beds. We need an agricultural bank to help people. We want a real bank of credit, not like the banks with high-interest rates we have now. We need schools across the country. We need to educate people on the environment, on medicine—on many, many other things. We need new ideas to bring these debates to all forty-three provinces so that we can make a new Haiti possible. We’ve already been working on a new constitution for a federal Haiti—it’s already a real subject of debate in the country. We need another society where the local will become global. We have to care about the localities, the little localities, so that they can survive—we have to give them money, give them credit. That’s what we’re talking about now: Haiti as one country, one big country, with forty-three provinces. You see, we’re talking a lot about decentralization because Haiti as a state is highly centralized, all the goods are coming into Port-au-Prince but not going back to the people. And that’s why we’re talking about a federal Haiti. People see that they have to be masters of their own fate in every province, not just subjects of what happens in the capital. We’re saying that people need to make projects for themselves in their own provinces because only they know what they need, what is good for them. I’m spreading this message by speaking out and through my music. We have a song on this, “Haiti Federal,” which we wrote several years ago. We did demonstrations in Gonaïves and other places about this idea of autonomy. We have to make changes, not just of the surface of things but their essence. Before the earthquake, the system was so old it had the mechanism to replicate itself. But now, afterwards, people are more aware. They see the need for change. They see that the state didn’t do anything and couldn’t do anything. At the moment that I’m talking to you now, I’m looking at my children and grandchildren here with me. We have to learn another thing for our children. We cannot go back; we have to go forward. My First-Hand Look at Post-Earthquake HaitiBy Jordan D. King July 4th, 2010 was one of the most powerful days of my life. It marked the beginning of a journey that would teach me, not only just how blessed I was, but also how important it was to be a blessing to others. This life-changing experience was a trip to Haiti, six months after the devastating January 12th Earthquake. It was something that I will never forget. The ten-day visit was to help my father shoot fundraising footage for the Haitian People’s Support Project. Led by founder Pierre Leroy of Woodstock, NY, this 22-year-old organization helps support nutritional, educational and development programs in the form of orphanages, schools and cooperatives throughout Haiti. Even before I met Pierre, who served as our guide, translator and host, my father warned me that I was in for a major culture shock. Yes, I was an African American male going to an island full of people of African decent, but the life I had known would be a world apart from the Haitians I’d see. He told me that my lifestyle as a New England boarding school student, who spent vacations with his mother in Texas, would end the moment we got off the plane. “You don’t know how good you have it,” he’d say – something I did not want to hear, and preferred to ignore. Just ten days in Haiti would completely change my outlook on life, and teach me the biggest lesson I have ever learned, which was to never take what I have for granted, and to give back. My first glimpse of Haiti, as my plane started to descend into Port-Au-Prince, was unforgettable. Instead of paved highways and skyscrapers, I saw roads in ruin and tin-roof houses everywhere. When I turned to my father in a state of disbelief, I believe he knew what I was thinking. “I told you,” he quietly said to me. As we exited the airport in the city that was the epicenter of the Earthquake, there was a fence protecting travelers from beggars. Hands reached out to us, some belonging to children no older than five. I was scared, not of getting mugged, but because I was so out of my element. Still, I had to remind myself that these Haitians, in the wake of the quake, were just trying to help their families survive. After all, their survival was the reason we were shooting the film footage. Later that day, we flew to Cap Haitien, the second largest city in Haiti. Though the January 12th Earthquake had not affected this city directly, it still felt like we were in a whole new world. As we walked up the street from the doctor’s home where we were staying, we found ourselves in an impoverished neighborhood. I saw children who looked like they hadn’t eaten in days and houses that appeared to be a-gust-of-wind-away from collapsing—images I thought only existed in movies. Back in suburban Dallas, I was used to seeing big, brick houses with lush green lawns. Yet, these people didn’t even have indoor plumbing. After filming in Northern Haiti, we flew back to Port-Au-Prince where it was hard seeing so many buildings completely demolished. I couldn’t believe that directly across from the collapsed Presidential Palace was a tent city. What affected me most, however, was coming across a rubble-filled lot where an apartment building once stood. There, we met a man whose two-year old daughter was missing her left arm. She lost it after their home caved in. But I soon realized she was lucky. The family of five who lived next door to them was killed during the Earthquake. Equally horrifying was hearing the story of a police officer whose arm was pinned under a building. Fearing the threat of aftershocks, he convinced a bystander to bring him a chainsaw, which he used to cut off his own arm. I believe the American public has a perception that Haiti is such a dirty place full of suffering. But few realize its beauty. For example, we took a bumpy truck ride through the mountainous rainforest to visit a beach called Labadee. The color of the ocean water was so blue, it contradicted my idea of Haiti being such a polluted place. Another spot that was breathtaking was The Citadel, a 19th century mountaintop fortress built by rebel slaves. As we made our ascent on horseback, it was hard to ignore the spectacular tree-covered mountain range. The view was nothing short of stunning. My time in Haiti was not easy psychologically or emotionally. In some sense, it was traumatic. I hated being followed by locals trying to sell me trinkets or begging for money. But I can’t blame them. Throughout history, Haitians have been through some of the toughest times conceivable. The January 12th Earthquake was just the latest chapter. Imagine everything being taken away from you in less than a minute. Imagine no indoor plumbing, running water, or electricity. Imagine roads, without traffic lights, that are barely drivable. Imagine losing limbs, parents, brothers and sisters. Then, imagine the power to make a difference. Haiti gave me that gift. My future plans may not be specifically clear. It may be that I return to the island to help rebuild homes, or establish a recreational program, or tutor in the schools. But one thing is for certain: I plan on following in the footsteps of Pierre and pledge to give back to the people of Haiti in some way. In the end, Haiti taught me not to take my life for granted. Even more importantly, it underscored the proverb that “We make our living by what we get, but we make our life by what we give.” My sentiments exactly. New Paltz EMT Tyler Moore works with Haitian childrenBy Jeremiah Horrigan WOODSTOCK — Terry Leroy breathlessly answered her cell phone. Breathlessness is a constant state of being for the diminutive co-founder of the Haitian People’s Support Project. She always seems to be revving her engines, even on the rare occasion when she’s idling, doing something — shopping for plants, in this case — for herself instead of for others. And maybe her energetic approach to life says something about the Haitian relief project and how the tiny, grass-roots group has brought financial, physical and emotional support to a place whose plight slipped from the world’s attention months ago. Here’s how an op-ed piece in The Los Angeles Times described the situation last week: “People suffer in ramshackle housing in overcrowded camps. Instead of facilitating imports of equipment, leaders have lapsed into a pattern of corruption and delay.” In the months since the earthquake rocked the country in January, Leroy, her husband, Pierre, and a handful of dedicated volunteer organizers, doctors and even local schoolchildren have been able to dodge the legendarily corrupt bureaucracy. Instead, they have built a small island of relief in an ocean of despair. The need is never-ending, and not unfamiliar to the Leroys, who established HPSP nearly 20 years ago. Terry Leroy recounts how a dozen volunteers on the island recently spent a day unloading a 40-foot container packed with staples such as rice and beans and with equipment such as 60 flashlights powered by expensive solar batteries. HSPS has sponsored benefits and roundtable discussions and has helped send not only medical supplies but also doctors and EMTs to the country. Local schoolchildren have collected hundreds of shoes and books through HSPS. But, while meeting immediate needs is critical, the group is also staying faithful to its long-term mission to promote self-sufficiency through training in a variety of disciplines. “We’re going to build a village,” Leroy said. The group will buy several acres of land and build 40 homes there. “I have to say we’re in a different place than the big agencies — we’re getting things done.” Ulster Couple Helps HaitiBy Jeremiah Horrigan But while Haiti’s seemingly intractable problems have continued to drift in the world’s back pages, Terry and Pierre Leroy, who live in the hamlet of West Hurley, have struggled mightily – and successfully – to keep an awareness of Haiti’s need in local focus. Their group, the Haitian People’s Support Project, has a long and deep relationship with Haiti, having supported five orphanages there for more than a decade. So their credibility was unquestioned when the Leroys began devoting their lives to helping the tiny country. Not that she’s complaining. When she speaks, she sounds like a kid in a candy store, astonished at what she sees, amazed at the generosity local people have shown to the HPSP. A CD featuring a number of high-profile local musicians has brought in $10,000. A brochure outlining the group’s efforts to raise money to combat cholera outbreaks has raised $25,000. “We’ve spent at least $110,000 so far, and we have more in the bank,” she said. “And we’ve continued to get large donations over the year.” She believes the group’s commitment to spend every dime it receives on relief efforts, including purchasing land for new settlements, providing medical and partnering with other low-profile, high-impact groups, has made them particularly attractive to donors. Some of these international agencies are hampered by both their own internal bureaucracies and the Haitian government’s, something PHSP doesn’t suffer from. A dance and art auction will raise funds for a beleaguered orphanage & other Haitian People’s Support efforts to help the poor island nation.By BONNIE LANGSTON

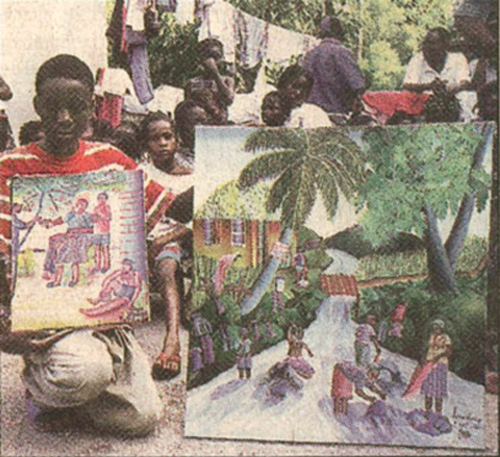

Vladimy Louis poses with two of his paintings at the House of Hope orphanage in Haiti. The untitled painting at the right is by Pierre-Jules Andre. Works by both teens will be sold at Friday’s fund-raiser.

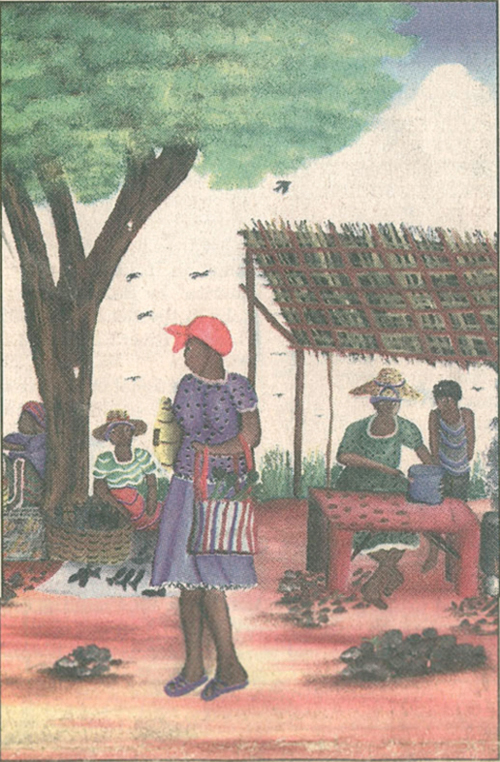

People at Market by Vladimy Louis

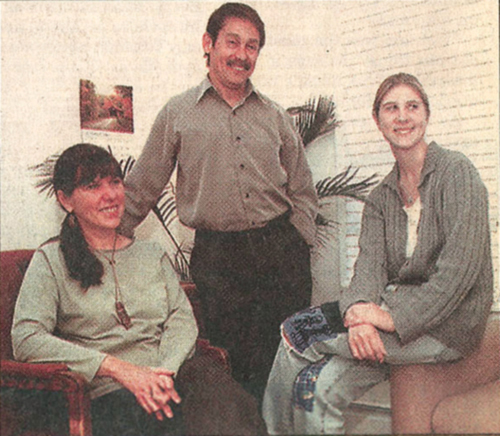

Joy Hopkins-Hausman, Bob Hausman and their daughter, Julia Hausman, are membersw of the Haitian Peoples’s Support Project and organizers of Friday’s benefit.

Untitled painting of a funeral procession by Vladimy Louis

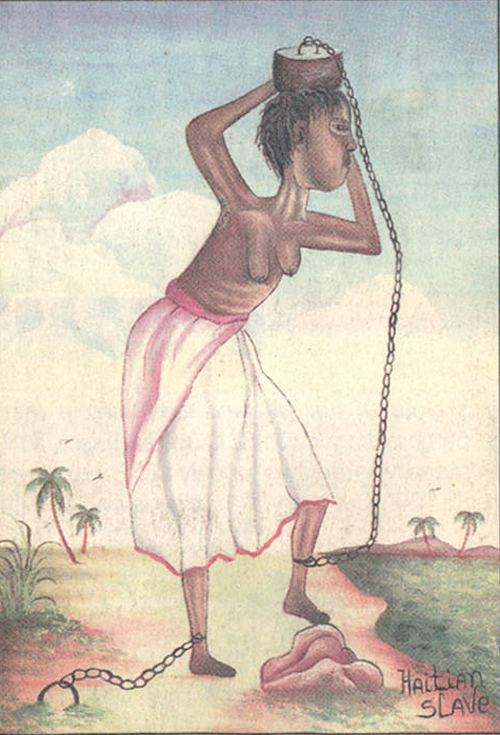

“Haitian Slave” by Pierre-Jules Andre

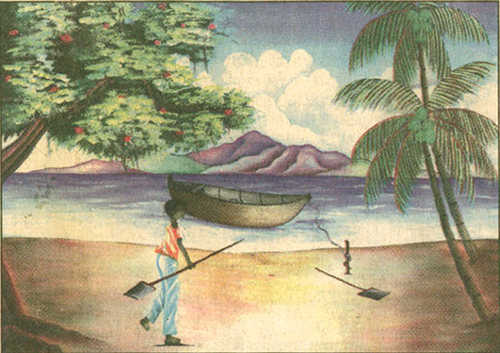

Boat People by Pierre-Jules Andre….. Despite the latest crisis, orphans at a children’s home in Haiti express their culture, ;life situation and dreams through their paintings – artwork slated for a silent auction at a fundraiser sponsored by the Woodstock-based Haitian People’s Support Project. The benefit is a dance that again features the Latin-beat band Sonando, starting at 9 p.m. Friday at Carambola/New World Home Cooking, Route 212 Saugerties. The silent auction, slated from 7 to 9 p.m., features the work of youths from Maison D’Espoir (House of Hope) an orphanage in Haiti that relocated earlier in the year because children there were terrorized by robbers. “Everything – even their food – was stolen,” said Joy Hopkins-Hausman, who along with her family has visited and offered support to the orphanage for the past three years. The children and staff were robbed three times. During one of the heists, a man held a gun to the head of one of the older orphans, demanding the key to a room in which a couple hundred dollars was stashed in a locked box. Finally, the founder of the orphanage lined up a truck and driver who drove all 90 of the children in the middle of the night to a hideaway about an hour away. Several months later the children were again relocated, to a southern suburb of Port-Au-Prince. “It’s safer now because it’s less remote,” said Pierre Leroy founder of the Haitian People’s Support Project, with his wife Terry. “There are more residential settings, more neighbors, there now.” About 50 percent of the money earned from the Friday benefit will go toward continued building at the orphanage and other efforts to improve the quality of life for the children who live there. A similar event earned about $4,000 last year, Leroy said, and he is hoping an equal or greater amount will come in this time. Leroy, born in Haiti, has been helping his people through the support project for 11 years with the assistance of others committed to the cause. The organization helps support a school, pottery co-op and peasant cooperative in the country as well as well as the group’s top priority. And for Leroy, commitment has always gone beyond sending money and supplies. He keeps tabs on the children with bimonthly reports, sending back encouragement, and rarely disapproval. “Every Christmas I go there, “he said. “The kids look forward to it. I do my silly little act of Santa Claus. I bring them goodies.” It was on one of those trips two years ago that Hopkins-Hausman, her husband Bob Hausman and their daughter Julia and son. Daniel fell in love with the children. But their living conditions – lack of electricity and water, for instance – stunned the family, along with five other support project members who joined them. The Hopkins immediately began work to help correct the situation. They wanted a better way of life for the children, including Pierre-Jules Andre and Vladimy Louis, whose artistic talent they could not help but recognize. It was Louis, now l8, who asked them to send art supplies to supplement the pencils he used for drawing. “He’s a real cool kid. He is a survivor,” Julia Hausman said. She learned that Louis, at the age of 7, had used his artistic skills to earn money to support himself and his dying mother. He used empty containers of powdered milk to fashion models of Haitian stoves, which he sold. As for Andre, Julia Hausman, 20 said one of his paintings is her favorite work in the silent auction. It is an untitled rendering of a boy in a small boat that appears to be going nowhere. “I think it’s the most touching in terms of the isolation,” she said. “It speaks about the experience of an orphan and the lack of options.” The youths’ colorful paintings include scenes from their life in Haiti, cockfights, the market and seaside, for instance. Most offer an idealized view, although a few, like the image of a funeral procession, are a strong statement about reality – life and death in this case. Another reality, as the orphans at Maison D’Espoir know full well, is poverty. “Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere,” Joy Hausman said. Art supplies are among the goods she and her extended family have been sending to the orphanage. The results? A seemingly unending stream of paintings the Hausmans decided to share with the community. Several are on view from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday until mid-December at the Woodstock Therapy Center, 15 Pine Grove St. in Woodstock, where Joy Hopkins-Hausman and Bob Hausman are directors and psychotherapists. “They’re prolific. They’re very prolific artists,” Joy Hopkins-Hausman said. “If they have the materials, they’ll paint… We’ve had a couple of art critics look at these, and they were impressed.” Indeed, the children themselves impress the Hausmans. They recalled a welcoming greeting that the youngsters, sang in English, instead of their native Creole, during the family’s first visit to the orphanage. “Most of them didn’t know what they were saying,” Hopkins-Hausman said. “Despite the fact they are so deprived, they are the most loving, high-spirited children.” The recent setback at Maison D’Espoir has been discouraging to the Hausmans, the Leroys and others, but they are determined to rebuild, to offer the children opportunity for a better life. Already dormitories have been built on the site. A kitchen, dining facility and office are also in use. Money from the benefit at Carambola will help provide a water pump so the children will not have to walk a quarter-mile to secure water. Other needs include additional electricity, classrooms and more bathrooms. Food, clothing, shelter, education and medicine are prime concerns. Nutrition is erratic; Bob Hausman said a condition he, his family and the Haitian Support Project are attempting to rectify. During the Jausman family’s first visit, they found the children eating cheese puffs and powdered milk for dinner. Later tests determined half were anemic. Beyond the basics, the Haitian People’s Support Project is committed to providing extended assistance through what is called the “Future Fund,” money earmarked largely for the children at Maison D’Espoir to learn a craft, start a business or other venture once they come of age. Ten percent of all donations to the support project go toward this fund. “It’s not only giving them life,” Julia Hausman said, “but resources to use life in a positive manner.” Meanwhile, her parents plan to return to Haiti early next year. The family has committed to five more years of support for a need they have seen first-hand, one that continues with the latest struggle to survive. “They’re in a crisis,” Joy Hausman said. “They’re dealing with a crisis and doing as well as you possibly could under the circumstances.” News from Haiti small miracle

Terry Leroy of West Hurley talks about the people she and her Haitian husband, Pierre, know, Pierre, know in Haiti, especially those in the orphanage they have supported for the past 16 years. BY JEREMIAH HORRIGAN Times Herald-Record WEST HURLEY – Like so many people with friends, or family members in Haiti, Pierre and Terry Leroy were living in a stunned state of suspended animation Thursday. Their roots in the devastated island are deep; the news they received was sketchy and rarely consoling. The West Hurley couple was concerned about the fate of 160 teachers and staff at the orphanage they have supported for 16 years. Maison D”Espoir (“ House of Hope”) Orphanage lies 40 minutes from Port- Au-Prince. “We don’t even know if it exists anymore, “Terry Leroy said early Thursday afternoon. Then at 3 p.m. Thursday, news came. Good news. The son of the orphanage’s 77-year-old founder called to say all the children and staff “were more or less OK – no one had died, Terry Leroy said. Against the grievous panorama of Haiti’s suffering this bit of news may seem small. But it was a miracle to the Leroys. Pierre Leroy grew up in Haiti – his cousin was briefly president of the country. But the reign of terror that was the “Papa Doc” Duvalier regime sent him to the U.S., where he met Terrry 35 years ago. The couple founded the Haitian People’s Support Project in 1990. Pierre Leroy would have been in Port- Au-Prince today for his yearly visit if the current government had not imposed an outrageously high customs charge for Christmas presents he usually sends to the orphanage. Other folks in the region were still hoping to hear from loved ones. Vincent Coq, who owns Shooters tavern in Port Ewen, is worried about his brother, who was attending a meeting Port-Au-Prince at the time of the earthquake. Even more critical, he said, were discouraging reports about his cousin, whose husband was able to reach her by cell phone in a collapsed building. ‘She was unable to speak, she was hurt and it was chaotic,” Coq said. Then the battery of her cell phone died. The Leroys hope they’ve found a way to directly and practically funnel support to the country. A team of former orphans now attending college in the nearby Dominican Republic are preparing to go overland to the stricken region. “It may be impossible, but we’re going to do belief work,” Terry Leroy said. She said how moved she was when earlier in the day she ran into a former colleague who, unbidden, gave her a check for $250.00. “I feel like I did when my mother died- in a zone – but when people reach out like that, it keeps you going. I feel reconnected to the human race. Hope for the children of HaitiHaitian People’s Support Project holds fundraiser at New World this Friday

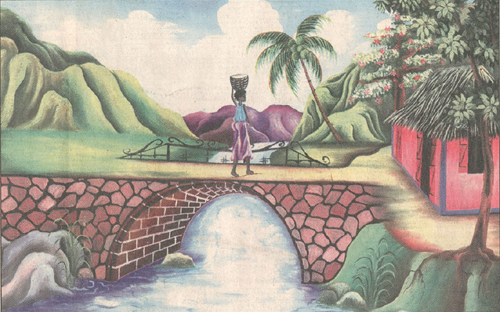

Most of the paintings that will be on sale at a benefit dance for Haitian children from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. on Friday. November 30 at New World Home Cooking on Route 212 depict the simple joys of life on the island Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic. However, their artists- children from the Maison D’Espoir (House of Hope) orphanage in Haiti and adult Haitian artists, whose paintings are being used to raise money for the facility – know another side of life there al too well. It is a life with 80 percent unemployment in which 75 percent of the population lives in abject poverty and the per capita GNP for the masses is about $300 a year, the lowest in the Western Hemisphere, according to UNICEF. Just a quarter of Haiti’s children enroll in school and less than half ever reach the fifth grade. There are bright spots amid such deprivation, however, and Maison D’Espoir is one of them. The orphanage was launched 12 years ago when Alice Barthole, a Haitian woman who now divides her time between Spring Valley and Haiti, took ten youngsters into her home. Within four years, there were 65 children living with her as word of her efforts spread. Today, the orphanage is home to 95 children, aged four to 18, and 13 adults. A year ago, the orphanage was forced to move to a safer and less remote spot some 20 miles outside of Port-Au-Prince after robbers had scaled the former facility’s eight-foot wall three times within a few weeks. An orphanage building has been constructed on the new site, a well is providing water, there is some electrical service and the children are in school, the younger ones at the orphanage’s on-site school and l4 older ones commuting to a nearby high school, according to Hurley resident Terry Leroy, a reading specialist for the Kingston Central School District, a co-founder of the locally-based Haitian People’s Support Project with her husband, Pierre Leroy, a French teacher at Roundout Middle School. The quality of life has steadily improved for these children but the needs at Maison D’Espoir remain enormous. The funds raised at Friday’s benefit with the Latin dance band Sonando will be used to provide inoculations for the youngsters and staff. A typhoid outbreak infected some of the orphanage’s children last year, but all survived and the community was able to contain what could easily have been an epidemic, say the Leroys. There has been a recent outbreak of polio in the region and the children are at risk to catch numerous diseases, including hepatitis. Classes at the orphanage are currently conducted in a pavilion. A real school with classrooms, a library and educational materials is needed, as is a more complete diet for the youngsters, who get very little protein. “If it wasn’t for us, a lot of these children would probably have died, concedes Barthole. Consider the story of Vladimy, Louis, a l9-year-old, who was just seven when he came to the orphanage. He supported himself and his dying mother at the time by making models from used milk containers and selling them on the street. Today, he expresses his artistic talents through brightly colored and skillfully executed paintings of everyday Haitian life that offer little hint of the emotional and physical distress he knew so intimately during his early childhood years. Ralph is another of the children at Maison D’Espoir. Abandoned at six weeks of age by his mother, he was brought to Barthole in an emaciated state with the distended belly that is characteristics of severe malnutrition. It remained unclear for some time whether the child would even survive. Now five. Ralph is still small for his age but is quickly becoming average in every way. On a recent day as members of the community laid a new path, he did his part by carrying a hat laden with small stones. He no longer cries at the sight of strangers and a comical twinkle now lights up his once somber eyes. It is interesting to see these kids come from very poor, disadvantaged backgrounds at the bottom of Haitian society,” says Pierre Leroy, “Many were abandoned. These kids are not aware of their pasts anymore, though. They don’t feel poor. They are happy. They have blossomed.”

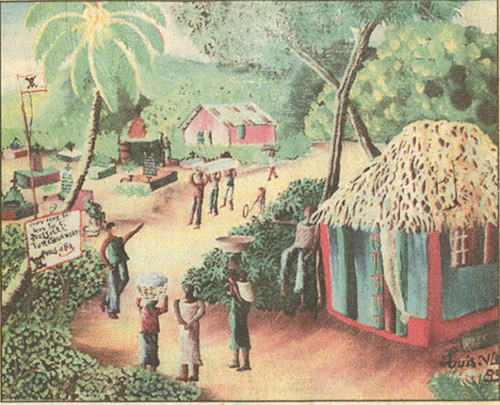

This painting by Haitian artist will be on sale this Friday at New World. The organization helps to support the orphanage in addition to several other projects elsewhere in Haiti, among them a pottery collective in central Haiti and a new school/community center/church facility on Haiti’s southern peninsula. “The children (at Maison D’Espoir) think I’m their father, Alice is their mother and anyone else who shows any interest in them is automatically drafted as a member of their family,” says Leroy. “They are starving for affection. That is why I tell people who send gifts to send notes too. They need the warmth.” Born to the very small stratum of privilege in Haiti, Leroy, 62, was the cousin of the country’s president. His father was Haiti’s finance minister. From the age of 10 to 16, he lived in the presidential palace. When the Duvalier, government came to power in the early 1960’s, Leroy could not ignore its fascist and corrupt bent. He joined a student strike and was forced to go into hiding and then flee to America. Included on a death list, he was unable to return to Haiti in the mid 1980’s as his mother lay on her deathbed. Leroy remained involved in the effort to democratize. Haiti and, with his wife, founded the Haitian People’s Support Project in anticipation of president Jean-Bertrand Aristede’s inauguration in 1991. The orphanage’s annual budget is some $77,000. In addition to the immunization program, Barthole and the Leeroys are currently seeking donations to purchase an adjacent plot of land next to the orphanage where hens would be raised for eggs and vegetables grown to balance out the children’s meager diet. Incredibly, the harsh conditions of life in Haiti do not spill over into the artwork that will be for sale at the benefit’s silent auction. In the case of the children, the art is often painted on the backs of tablecloths and bits of painting that have been stretched over makeshift frames due to the lack of art supplies. The scenes are almost incomprehensibly idealistic in view of the tribulations the children have experienced. Their innocence is palpable. The orphanage has received substantial donations in recent years from the Living Word Chapel on Route 28 and from Woodstock residents Joy and Bob Hausman and their relatives. Virginia church provided the funds to purchase the new site. Joy Hausman’s brother, Stephen Hopkins, a Washington D.C.-based political scientist who works as a consultant in third world countries, helped to create a “Future Fund” to enable the orphanage’s older children to learn a trade or start a small business when they leave the facility. The youngsters earn credits through their work at the orphanage that can be cashed in when they leave as young adults. The Hausmans believe their family’s efforts can serve as a model for the service projects other families choose to adopt. They say they have found their participation so rewarding, they often feel like the beneficiaries. The Leroys and Barthole take groups of volunteers with them to the orphanage several times a year. The nest trip will depart on December 22. Another trip is scheduled in April. The cost is approximately $500 for roundtrip airfare plus a donation for food. Lodging is provided. Individuals wishing to make a donation to the Maison D’Espoir orphanage can send it to the Haitian People’s Support Project, PO Box 496, Woodstock, NY 12498. For more information call the Leroys at 679-7320 or Barthole at 425-5611. Andrea Barrist Stern |

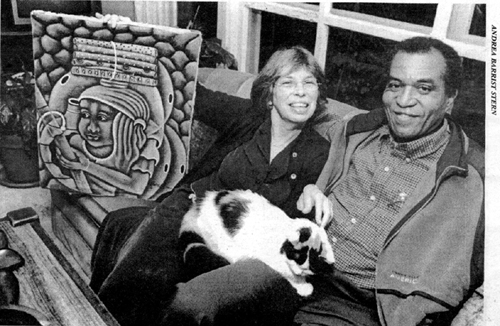

Hurley resident Terry Leroy, with her husband, Pierre Leroy, co-founders of the locally-based Haitian People’s Support Project.

Hurley resident Terry Leroy, with her husband, Pierre Leroy, co-founders of the locally-based Haitian People’s Support Project.